|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

My First Job

As a young girl, I attended schools in several European countries and Israel. After marrying and moving to a New Jersey suburb in the early 1960's, I began graduate school in Library Sciences at Columbia University in New York. I chose this field for two reasons: first, I was an avid, passionate reader. Second, the class schedules were flexible, enabling me to enjoy and take care of my husband and two preschoolers. Ironically, I graduated from Columbia with a Masters in Library Science before mastering the English language.

Anxious to make use of my newly acquired skills and diploma, I began to jobhunt. I called potential employers, but my lack of experience and my heavy Polish accent were no help. One day, I spied a notice on the bulletin board at school. The New York Academy of Medicine needed a cataloger. The position required experience, attention to detail and a knowledge of foreign languages. Although I knew many languages, I had no relevant experience, and no hope of getting even an interview. Still, I submitted my resume. To my surprise, I was granted an interview. I hired a babysitter and ventured into Manhattan on the appointed day.

The New York Academy of Medicine is one of the most prestigious institutions of its kind in the United States and, perhaps, in the world. Upon entering the building of the Academy, a doorman directed me to an elevator, and then I walked through dark, paneled walls lined with old books. At the end of the corridor, an older diminutive lady greeted me. Her name was Miss Farrington, and she was the head of the cataloging department. She stood just under five feet tall and spoke with a slow British accent. She drew me into a private office, carefully closed the door, and began asking questions. She did not ask about my education or work experience. Instead, she asked about my last name (Frisch), my husband's first name, his place of birth, his parents and his ancestors. Unfortunately, I had little information. I never met my in-laws. They were killed by Nazis during World War II and I knew nothing of my husband's extended family. Most of them also perished at the hands of the Nazis. The interview seemed strange and unproductive. Before parting, Miss Farrington asked, "Do you want this job?" "Sure," I answered. "It is yours," she replied.

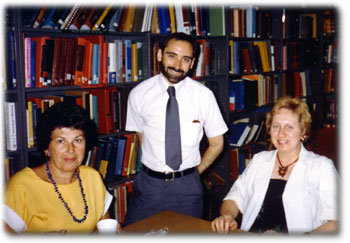

Irene Frisch (left) with 2 colleagues at work.

Roughly one hour later, I arrived home. The babysitter handed me a telephone number and advised me to return the call immediately. It was Miss Farrington's secretary. She needed several details not covered in the interview. A few days later, I received a letter from the Head of the Academy confirming my employment and stating my salary, hours and benefits. Even today, I do not know how Miss Farrington arranged my hiring. There should have been many people to consult before hiring a new staff member. Somehow, she broke all barriers. I still have that letter.

Miss Farrington was demanding, and did not allow anyone special privileges. I had to make up even three or four minutes when I was late to work. But Miss Farrington was also an excellent teacher and mentor, and the cataloging job at the Academy was a career door-opener. After one year, I left the Academy and found work in the library of a hospital near my home, thus saving two hours of commuting each day and allowing for more time with my family.

Miss Farrington was deeply saddened by my departure. She had never married or had children of her own, and during that short year, she had become a kind of surrogate grandmother to my children, often babysitting or visiting. I had also become her confidante. I learned that she was born and raised in Vienna and, most significantly, I learned that her original name was Frisch, the same as my husband's! Her father died when she was a child, and her relationship with her mother soured over the years. She moved to London at a young age. Desperate to assimilate, she changed her name to Farrington, and her accent to English, and severed ties to her mother and her past. She later learned that her mother was killed during World War II. Time passed, but did not allay her guilt over abandoning her mother. Many years later, she confessed to me her reason for hiring me: she could not "abandon" another Mrs. Frisch.

Miss Farrington and I maintained a close relationship over the years and I was given her family photographs and personal affects upon her death. Certainly, my education at a prestigious university qualified me to work as a librarian. But it was a strange, sad coincidence that created an opportunity for my successful, thirty-year career as a librarian.

October 29, 1996